She was joined by her monkeys and parrots, as her back problem, which had been caused by her being impaled during a bus accident as a teenager, had developed to such an extent that she could neither stand nor sit for any length of time.

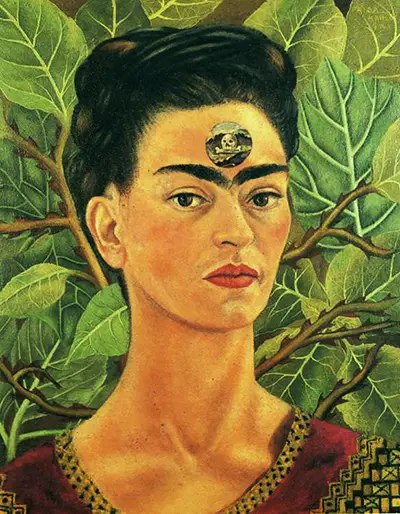

In the painting she stares out unflinchingly against a backdrop of luxuriant foliage. In the centre of her forehead, just above the two dark bushy eyebrows, is a perfectly circular round hole, within which is a rural landscape dominated by a skull and crossbones.

The face is neither frightened nor filled with despair; it is calm. She seems to say that if death and suffering can be accepted as a natural part of life then fulfilment is possible. It is one of her many self-portraits that relentlessly lay bare her pre-occupations with death and her own physical fragility.

It demonstrates her fearlessness in confronting what lies at the centre of existence: death.

By putting death in the place of the third eye, the chakra, she makes it the source of all wisdom. Despite the apparent strangeness of this and many of her other images, she rejected being labelled a "surrealist" insisting that what she painted reflected not her dreams but her reality.

Andre Breton, the French surrealist, said of her art: it is a "ribbon around a bomb." She said, "I paint myself because I am so often alone and because I am the subject I know best." She was born in Mexico, July 6, 1907.

As a child she suffered from polio and as a teenager was in a near fatal bus accident. As a consequence of these two events she was dogged with illness and physical suffering for her entire life, spending long periods of time recuperating in isolation. She died July 13, 1954.